Threats to Qui Tam False Claim Suits

By Samuel May Oct 06, 2023

By Samuel May Oct 06, 2023

Qui tam pro domino rege quam pro se ipso in hac parte sequitur

He who sues in this matter for the king as well as for himself.

The legal notion of qui tam can be traced back to the Romans. Originally, Roman law allowed private individuals to initiate criminal prosecutions, offering citizens a portion of a defendant’s forfeited property as reward for bringing successful suits in the government’s stead. Codified in English Law sometime in the Middle Ages, qui tam actions allowed for private individuals to enforce the King’s law, ostensibly to extend enforcement of the law into areas or regions where a public police force was lacking. One can be forgiven for thinking the Latin phrase originated with the Roman law, but it was a creation of English lawyers, with most modern references extending only as far back as Blackstone’s, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” from 1768.

Qui tam actions existed at the genesis of the United States, as many individual states overtly copied over existing British law (which at the time included qui tam provisions) or enacted laws mirroring their British counterparts. Further, the First Congress of the United States included qui tam provisions in several statutes.

The prevalence and use of qui tam, however, saw continual change over the proceeding centuries. Criminal enforcement through qui tam saw more limitations both in the U.S. and the U.K. In what was described as a “steady erosion of the informer actions” rather than a “concerted effort to abolish”, qui tam was either removed from statutes through legislative action or simply employed with less frequency. By 1943, U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals judges and Supreme Court justices revealed through separate decisions a division on whether qui tam suits were generally “regarded with disfavor” or “frequently permitted by legislative action” and defended by the courts.

The use of qui tam seems, therefore, to be intrinsically linked to the prevalence of fraud and the ability of the government to effectively combat it. Where the state actors (whether that be the King’s men or state police) were insufficient or unable to satisfy the public need for enforcement, private citizens were empowered to bring suits to enforce the law on the government’s behalf.

The False Claims Act (FCA) was signed into law in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln. At the time, fraud against the federal government was rampant. Inferior equipment was being sold and supplied to Union troops fighting to keep the country together. With insufficient federal manpower to pursue the fraudsters, qui tam actions were once again authorized to buttress enforcement. The FCA at this time allowed, but did not require, the government to provide financial incentives to private citizens who sued on the government’s behalf.

It was only in 1986, when the government was again facing significant occurrences of fraud in military spending, that a bipartisan amendment created the qui tam structure we have today. The key provision of this amendment to the FCA was the guarantee, not just the allowance, of payment to whistleblowers who brought a successful suit.

The FCA was further strengthened in 2009 with the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act and in 2010 with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

In 2012, these additional qui tam provisions were being heralded as “nothing short of profound” by the U.S. Attorney General.

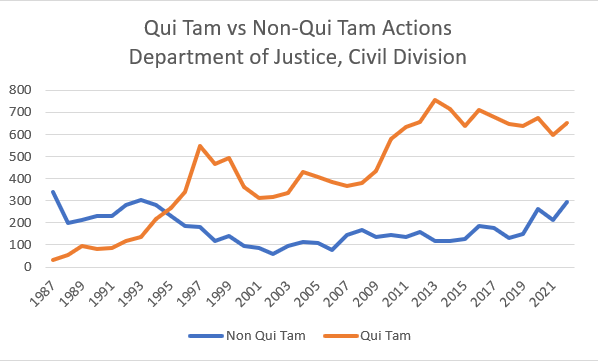

Image 1- https://www.justice.gov/d9/press-releases/attachments/2023/02/07/fy2022_statistics_0.pdf

Of the $2.2 billion in False Claims Act settlements and judgements reported by the Department of Justice in fiscal year 2022, $1.9 billion related to suits filed under qui tam provisions. That number includes suits pursued by the whistleblower entirely and those taken over by federal intervention. $488 million was paid out to whistleblowers involved in the 2022 suits. The best year for FCA recoveries was 2014, when the DOJ saw $6.1 million in settlements and judgments. Qui tam made up $4.48 million (or more than 70%) of that total.

Recent opinions from the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) have cast a shadow over the qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act. While no controlling, majority opinion from SCOTUS has diminished the FCA, several dissents have laid the groundwork for future cases to directly attack the ability of whistleblowers to bring suits on the government’s behalf.

The line of argument is not a recent phenomenon. In Riley v. St. Luke’s Episcopal Hosp. from 2001, two Circuit Court judges crafted a dissenting opinion in a FCA case, stating explicitly that qui tam actions where the government declines to intervene violate Article II of the Constitution and the Separation of Powers.

The more recent dissenting opinion comes courtesy of Justice Clarence Thomas in United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources from June 2023. Justice Kavanaugh and Justice Barrett included in their concurring opinion that they agreed with Justice Thomas that there are “substantial arguments that the qui tam device is inconsistent with Article II.”

In Polansky, Justice Thomas lays out his reasoning to question the constitutionality of the FCA’s qui tam provisions, but he also lays the foundation for counterarguments to any defense of the nearly 160-year-old law.

First, Justice Thomas suggests that the qui tam provisions violate the “Take Care Clause” from Article II § 3 of the Constitution: The Executive “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” This power includes the authority to investigate and, importantly, litigate any offenses against the United States. Justice Thomas argues that allowing individual citizens to bring suit under qui tam provisions transfers this Executive responsibility, and accountability, away from the Executive. Justice Thomas goes on to suggest that Congress, in passing the qui tam provision, undermines and reassigns the power of the Executive without authority.

Additionally, Justice Thomas asserts that the qui tam provisions violate the Appointments Clause, Article II § 2, as the qui tam relators are not officially appointed by any branch of government, including the Executive, and are not officers of the United States when they bring whistleblower suits. Any suit brought “by” or “for” the United States, Justice Thomas argued, should be brought by an officer of the United States.

As to the counterarguments, Justice Thomas includes in his dissent a section entitled “History Is Not Controlling.” In this section, Justice Thomas raises and refutes certain foreseeable defenses to the qui tam provisions. Justice Thomas recognizes that legislation was passed by the First Congress of the United States with qui tam provisions included but suggests that these laws were “passed quickly and without deliberation as to their constitutionality” and were too different from the FCA. Justice Thomas also reminds the reader that virtually all qui tam laws from this era were diminished and eventually removed. Justice Thomas also recognizes the use of qui tam during times of “great exigency,” but suggests that “Today the Executive is anything but weak” and “there is no [current] need to deputize private citizens to prosecute the claims of the United States.”

The dissent, and especially the concurring opinion by the two other justices, essentially served as a call to action, requesting a new case with facts specific to this issue. The call was answered almost immediately.

On August 17, 2023, a motion to dismiss was filed in the Northern District Court of Alabama in Us ex rel. brooks Wallace, Robert Farley, and Manuel Fuentes v. Exactech Inc. The motion requests the court to dismiss the suit against Exactech because the False Claims Act fundamentally violates Article II of the Constitution. The brief cites Riley and references the Supreme Court dissent authored by Justice Thomas: “Justice Kavanaugh, joined by Justice Barrett, wrote that the Supreme Court ‘should consider the competing arguments on the Article II issue in an appropriate case.’ […] This is that case.”

Additionally, on September 6, 2023, in a whistleblower suit against Planned Parenthood, the defendant moved for the court to dismiss the suit, stating that the qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act violate the Appointments and Take Care Clauses of the Constitution. The motion also argued that two state laws that include qui tam provisions violate the state constitutions of Texas and Louisiana, respectively.

It will take time for either of these two new cases (or any of the others soon to crop up with similar arguments) to reach the Supreme Court. Once a case does, however, make it through the appeals process and is accepted for review by the Court, there appears to be little hesitancy from at least several members of that court to declare the qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act to be unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has all too recently proven that it is willing to overturn precedent and what was thought to be settled law where it has determined unconstitutionality exists. While “History Is Not Controlling,” the significant and beneficial impact qui tam suits have had in helping to combat fraud and reward whistleblowers for bringing fraud to light will hopefully be considered.